This post is a summary of the paper “Extending the natural adaptive capacity of coral holobionts” 1 written in my own words, using my own understanding of the content. The primary purpose of this summary is to expand and solidify my own knowledge on these topics. Although this summary is about the paper “Extending the natural adaptive capacity of coral holobionts”, there are a number of additional citations either from the citations sources used in this paper or were used by myself to better understand the contents of the paper.

This paper gives a substantial and thorough review of existing and evolving intervention methods for coral reef restoration efforts. It specifically focuses on intervention methods that expand coral’s natural ability to adapt to small changes in environmental conditions. By expanding these natural abilities, the hope is that we may be able to help coral adapt quickly enough to have a chance at surviving climate change. These intervention methods are evaluated based on effectiveness (long term and short term), feasibility, and scalability.

The first principle emphasized in this paper is the concept of the coral holobiont. The coral holobiont is a complex system of organisms that live together in a coral, including the coral animal and many other symbiotic partners. 2 In order for any intervention utilizing corals’ natural adaptive abilities to be successful, the whole coral holobiont must be included.

The image below illustrates the key players in the coral holobiont. The arrows and numbers illustrate the known and inferred relationships and interconnections between the organisms involved. Bolded numbers represent inferred relationships and non-bolded are the known relationships.

Adaptive strategies of Coral

Coral organisms have a number of natural adaptive strategies that are explored and summarized in this paper.

- Acclimation: Coral can adjust on a physiological level to environmental stress conditions, however the full capacity of this ability is not fully understood.

- Evolutionary adaptation: As with all organisms, over the course of many generations, natural selection will affect changes in coral species that are more favorable for the existing environmental conditions.

- Environmental hardening: Individual corals exposed to incremental amounts of environmental stress have demonstrated an ability to adapt on a physiological level.

Several intervention methods have been developed that use these natural adaptive abilities of coral.

Ex situ spawning

This method involves taking individual coral specimens into a lab setting and recreating the conditions for coral spawning. This is an effective method for selectively breeding thermal tolerant individuals as well as a stop-gap measure for areas where coral cover is so reduced that spawning would not result in fertilization.

Coral Bleaching Automated Stress System (CBASS)

This is a recent development in research and interventions for thermal stress. It is “a low-cost, open-source, field-portable experimental system for rapid empirical assessment of coral thermal thresholds using standardized temperature stress profiles and diagnostics”. 3 This system allows researchers to quickly identify individual corals and coral species that are strong candidates for selective breeding and environmental hardening as well as relocation to areas where coral have died in bleaching events.

Selective breeding:

On the surface, this is a fairly straight-forward method. Coral individuals with higher thermal tolerance are bred to produce more resilient offspring. There is evidence that thermal tolerance can increase by up to five times if even one parent has greater thermal tolerance. However, some coral species take this evolutionary capacity one step further with some amazing genetic capabilities. Certain coral species can turn certain genes on or off to literally change their phenotype in response to environmental stressors and then pass that change on to their offspring. This means that these coral potentially have the ability to speed up their own process of evolutionary adaptation. This phenotypic change is called transcriptomic change and the one most commonly associated with changes due to environmental stressors is called DNA methylation. 4 5

Ex Situ Environmental hardening

Individual corals in a lab setting can be exposed to small amounts of environmental stress that slowly increases until it matches current conditions. This method of slowly exposing coral to thermal stress gives the organism time to adjust and adapt. Once the adjustment is done, these coral have a much higher chance of survival during future heat waves. These coral are then outplanted to areas where bleaching events have occured to restore dead or dying reefs. This acclimation method combined with DNA methylation can be a powerful and effective method of establishing thermally resilient coral reefs.

Cryopreservation:

This method is more about preserving genetic diversity until researchers can find a way to establish healthy, resilient reefs under the new conditions of climate change.

The authors of this paper assert that the most promising and practical approach is to screen coral larvae for thermal tolerance before they settle and using these individuals to repopulate reefs.

Symbiodinaceae Adaptive Strategies

Symbiodiniaceae are the microalgal photosymbionts of shallow water coral. They provide over 90% of the energy coral needs to live and in return, receive easy access to sunlight from a protected position within the cells of the coral tissue.

When subjected to thermal stress, these microalgae experience “increased production of superoxide radicals leading to oxidative stress” 6 which, when sufficient levels are reached, will cause the coral to expel the symbionts thus resulting in a bleaching event.

There are hundreds of different symbiodiniaceae species within this family corresponding to the high level of host-symbiont specialization. Although some species of symbiodiniaceae are more thermal tolerant, there has not been a great deal of success getting new host-symbiont pairings to stick. Most intervention methods have not persisted past the generation receiving the treatment. Therefore, more effort is placed on interventions that will result in heritable changes.

In a lab setting, symbiodiniaceae exhibit short-term adaptive changes and possess many traits that enable them to undergo rapid evolutionary adaptations including short generations, sexual and asexual reproductive modes, and “genomic adaptive precursors such as extensive functional enrichments, mobile elements, and RNA editing“7 In nature, symbiodiniaceae exhibit lifecycle patterns in keeping with geographic isolation and local selection which greatly increases the process of local adaptation. However, even the most heat-tolerant symbionts can only increase thermal tolerance by about 2°C which will be far exceeded within the next 100 years.

Prokaryote Adaptive Strategies

Prokaryotes, which include bacteria and archaea (obligate anaerobic single-celled microorganisms with a structure similar to bacteria) form the coral microbiome and play an important role in the health and fitness of coral hosts. In fact, there is a “coral probiotic hypothesis” that seeks to explain this relationship;

“The basic concept of the Coral Probiotic Hypothesis is that the coral animal lives in a symbiotic relationship with a diverse metabolically active population of microorganisms (mostly bacteria). When environmental conditions change, e.g. increased seawater temperature, the relative abundance of microbial species changes in a manner that allows the coral holobiont to adapt to the new condition.” 8

The implications of the hypothesis are the potential to alleviate stress, increase bleaching recovery rates and times, increase disease resistance, and ease the stress of toxins and pollutants with the application of “Beneficial Microorganisms for Corals” (BMCs). Though this is a somewhat new area of study, there have been proof-of-concept studies that show success in mitigating stress relating to toxin and pathogen exposure. Many challenges remain regarding the longevity of the interventions and the scalability of this method.

Viral Adaptive Strategies

There is evidence that bacteriophages – which are numerous in the coral holobiont – act as an immune system by attacking and ridding the coral of unwanted or harmful bacteria. Viruses can also affect the evolution of coral through lateral gene transfers wherein genetic material gets transferred or otherwise changed such that it becomes heritable. However little is understood about this method. There are a number of methods used in other fields that could be applied to coral interventions but they are not fully researched and each come with risks that could be significant in a reef ecosystem.

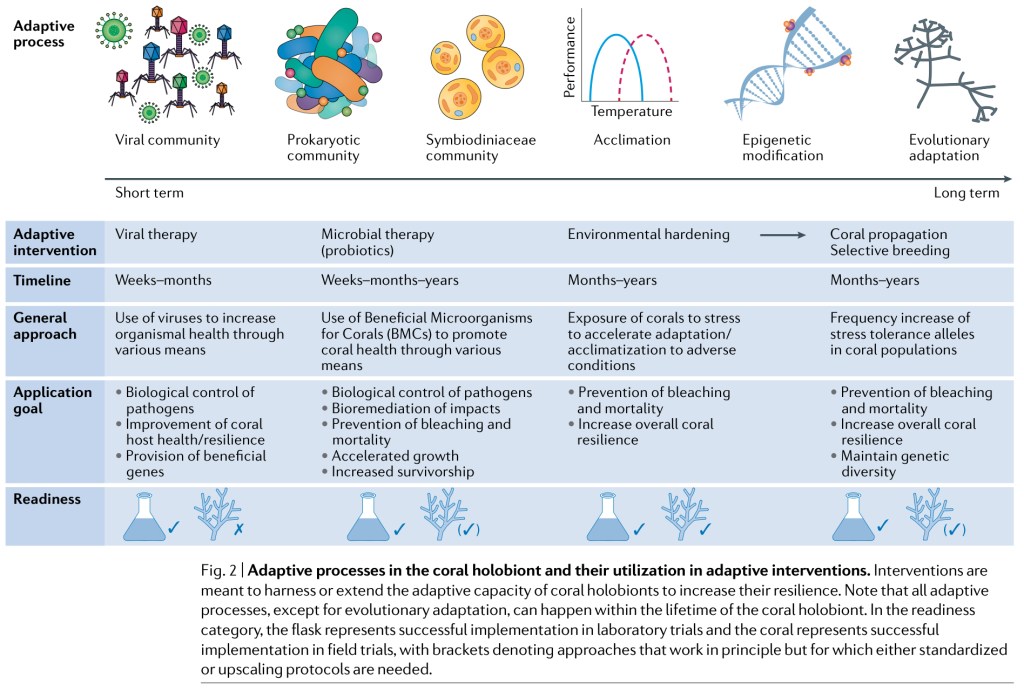

The image below lists each of the adaptive capacities of the coral holobiont and an assessment of its deployment readiness, scalability, costs, and risks.

Adaptive Intervention Framework

This paper emphasizes the need to view coral restoration as environmental rehabilitation, defined as the “action of restoring to an improved condition to allow species and ecosystems to thrive under altered conditions” 9 as opposed to trying to recreate the reefs as they once were. Instead, emphasis and effort should be placed squarely on using adaptive interventions to enhance the functional and genetic diversity of the reefs as they are now in order to keep enough of our coral reefs that they stand a chance at long-term recovery.

The image below gives a quick overview of the adaptive interventions discussed in this paper, an implementation timeline, a brief description of the method, the application goals, and the readiness of the method. In the readiness row, the flask indicates a lab setting and the coral indicates the field. A checkmark next to the flask or coal indicates this is ready while an ex means it is not. The parenthesis indicate that standardized or upscaling protocols are still needed. Thus far, only environmental hardening is fully field ready.

Extending natural adaptive capacities

Each of the methods outlined in this paper entail some degree of risk that varies depending on the method. This risk can be greatly reduced by focusing on intervention methods that use the natural, pre-existing capacities of the coral holobiont. It is therefore, crucial that future research is focused on better understanding the interactions of the member species that make up the coral holobiont.

Additionally, these adaptive intervention methods should be used in cooperative and strategic combinations to maximize overall effectiveness. For example, screening coral larvae and juveniles for thermal tolerance combined with environmental hardening of the selected individuals will give the coral a significantly increased chance of survival. These combinations can happen at many different levels and at different stages depending on scalability, cost, and existing infrastructures.

Scalable intervention framework

Scalability is a key factor in effectiveness for interventions if we are to match, let alone exceed, coral mortality rates worldwide. Currently, worldwide there is still a great deal of focus on asexual fragmentation and outplanting. This method alone does not increase genetic diversity and is costly and time-consuming. However, in combination with other intervention methods, this can be much more effective.

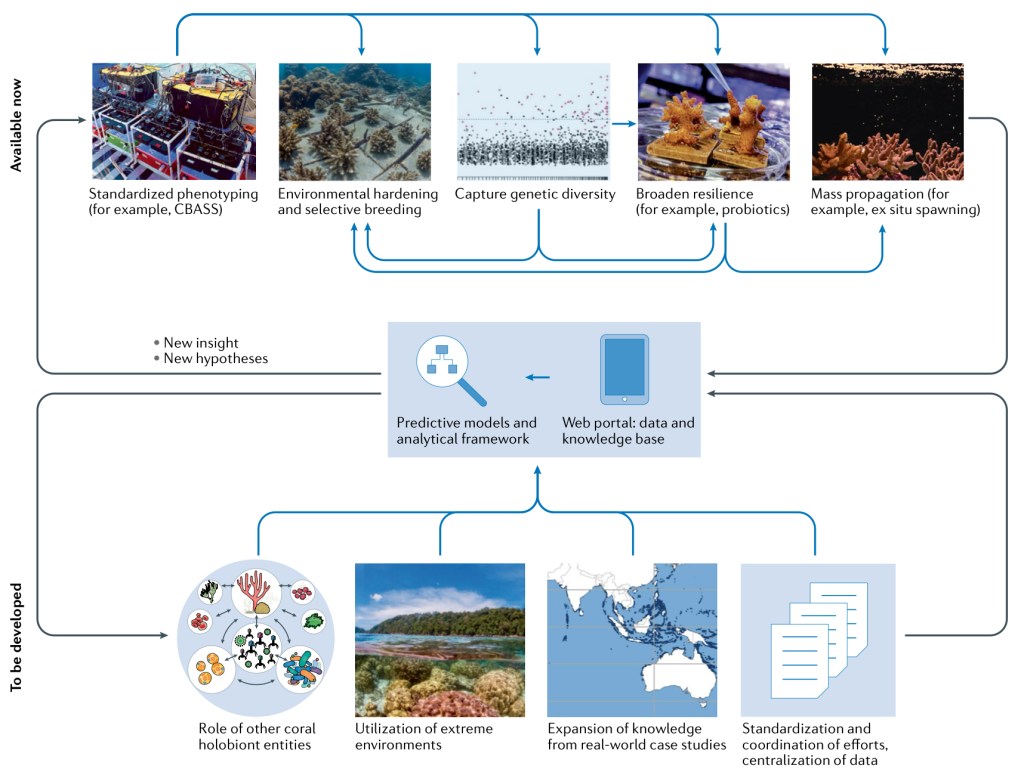

The image below gives a graphical illustration of the recommendations from this paper for the development and implementation of standardized monitoring methods, standardized diagnostics, and a decision-making framework.

Research Roadmap

The image below is a graphical illustration of the proposed research roadmap in this paper. The upper half illustrates the emerging intervention methods. The blue arrows indicate methods for coral restoration, the arrow direction shows the ways in which methods could be integrated and coordinated for greater impact.

The lower half of the illustration depicts areas in need of further research. For example, there is a need for better understanding of the coral holobiont given it is currently not know how much interventions focused on the coral holobiont affect the reef as a whole over time.

While these intervention methods are critical, it is also important to note that no amount of intervention can help without ongoing efforts to mitigate climate change and improve water quality.

Summary

Currently, the global coral mortality rates and reef degradation rates are higher than what we can effectively respond to. If we are to have a chance at successfully rehabilitating our reefs, research must focus on extending the adaptive capacity of coral “through integration of novel tools, methods, and environments that are studied to increase the survival of coral under more extreme or variable conditions”. 10 These efforts will benefit greatly from standardization but must also be able to accomodate the specific local needs and conditions of a given reef ecosystem.

This paper outlines the following four areas in which future research could increase chances of successful reef rehabilitation:

- Gain a better understanding of the coral holobiont; there is potential here to increase coral resilience during times of stress and improve overall effectiveness of other intervention methods long-term.

- Use extreme environments to learn more about the evolutionary adaptations of organisms in those environments in order to determine whether these could be applied elsewhere.

- Expand our knowledge of the real-world impact of interventions via case studies.

- Apply intervention methods using standardized and coordinated efforts in order to assess the feasibility, scalability, efficacy, and associated risks more quickly.

Citations:

- Voolstra, C.R., Suggett, D.J., Peixoto, R.S. et al. Extending the natural adaptive capacity of coral holobionts. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2, 747–762 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00214-3 ↩︎

- Thompson JR, Rivera HE, Closek CJ, Medina M. Microbes in the coral holobiont: partners through evolution, development, and ecological interactions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2015 Jan 7;4:176. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00176. PMID: 25621279; PMCID: PMC4286716. ↩︎

- Evensen, Nicolas. Parker. Katherine E. Oliver, Thomas A. Palumbi, Stephen R. 2023. The Coral Bleaching Automated Stress System (CBASS): A low-cost, portable system for standardized empirical assessments of coral thermal limits. Limnology and Oceanography: Methods. 21(7). DOI:10.1002/lom3.10555 ↩︎

- Liew, Y.J., Howells, E.J., Wang, X. et al. Intergenerational epigenetic inheritance in reef-building corals. Nat. Clim. Chang. 10, 254–259 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0687-2 ↩︎

- Crowley, Natalie. February, 2020. Epigenetics May Help Rebuild The Coral Reefs. Environment, News & Reviews. What is Epigenetics. https://www.whatisepigenetics.com/epigenetics-may-help-rebuild-the-coral-reefs/ ↩︎

- Nedeljka Rosic, Jérôme Delamare-Deboutteville, Sophie Dove. 2024. Heat stress in symbiotic dinoflagellates: Implications on oxidative stress and cellular changes. Science of The Total Environment. Volume 944. 2024. 173916. ISSN 0048-9697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.173916. ↩︎

- Voolstra, C.R., Suggett, D.J., Peixoto, R.S. et al. Extending the natural adaptive capacity of coral holobionts. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2, 747–762 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00214-3 ↩︎

- Reshef, Leah. Koren, Omry. Loya, Yossi. Zilber-Rosenberg, Ilana. Rosenberg, Eugene. 2006. The Coral Probiotic Hypothesis. Environmental Microbiology. 8. 12. 1462-2912. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01148.x. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01148.x. 2068. 2073. 2006 ↩︎

- Voolstra, C.R., Suggett, D.J., Peixoto, R.S. et al. Extending the natural adaptive capacity of coral holobionts. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2, 747–762 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00214-3 ↩︎

- Voolstra, C.R., Suggett, D.J., Peixoto, R.S. et al. Extending the natural adaptive capacity of coral holobionts. Nat Rev Earth Environ 2, 747–762 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-021-00214-3 ↩︎