Coral Bleaching Automated Stress System (CBASS) was developed in 2020 and 2021 by Dan Barshis and Tom Oliver. CBASS is a standardized, low-cost, portable experimental system that uses customizable temperature control and flow-through aquaria to conduct standardized empirical assessments of coral thermal limits.1

This is a summary of the paper “The Coral Bleaching Automated Stress System (CBASS): A low-cost, portable system for standardized empirical assessments of coral thermal limits” by Evansen et al. which gives an in-depth explanation of CBASS purpose and functionality.

In response to the growing need to identify coral genotypes with greater resilience to thermal stress and bleaching, the CBASS system was conceived and developed in order to help identify thermal resilient coral genomes. These coral individuals are crucial to conservation efforts; whether identifying which individual coral should be outplanted in restoration projects or used as broodstock for selective breeding projects.

The purpose of CBASS is to enable widespread standardized comparison of corals thermal thresholds in order to identify the individual genes that have the best chance of surviving climate change

Prior to the development of CBASS, there was no standardized procedure to evaluate individual corals or populations for any kind of resilient capacities. Researchers were limited to observational surveys during naturally occurring bleaching events, which is a slow, expensive, and inconsistent method – especially when attempting to compare across different regions, ecosystems, coral populations, or coral species. These observational survey results were also affected by other anthropogenic factors including pollution levels, and degree of human disturbance, to name just two examples.

In addition to the differences in regions and ecosystems, the local communities surrounding each coral reef location varies widely in terms of resources, infrastructure and capacity to implement observational surveys.

CBASS was designed to be a low-cost, approachable systems whose reliable methods are transparent and easily understood. This system is highly portable, self-contained, and allows for deployment in almost any setting where seawater is available – either by pump or by hand – and some amount of electricity – either electrical grid or portable generator – is available. This means that remote locations, ship based operations, and small communities could actually use this.

In addition to being an affordable, portable, easy to use system, CBASS utilizes an open source platform (Arduino) for the controller electronics, and includes a set of standardized, thermal profiles, and analytical routines.

System Overview

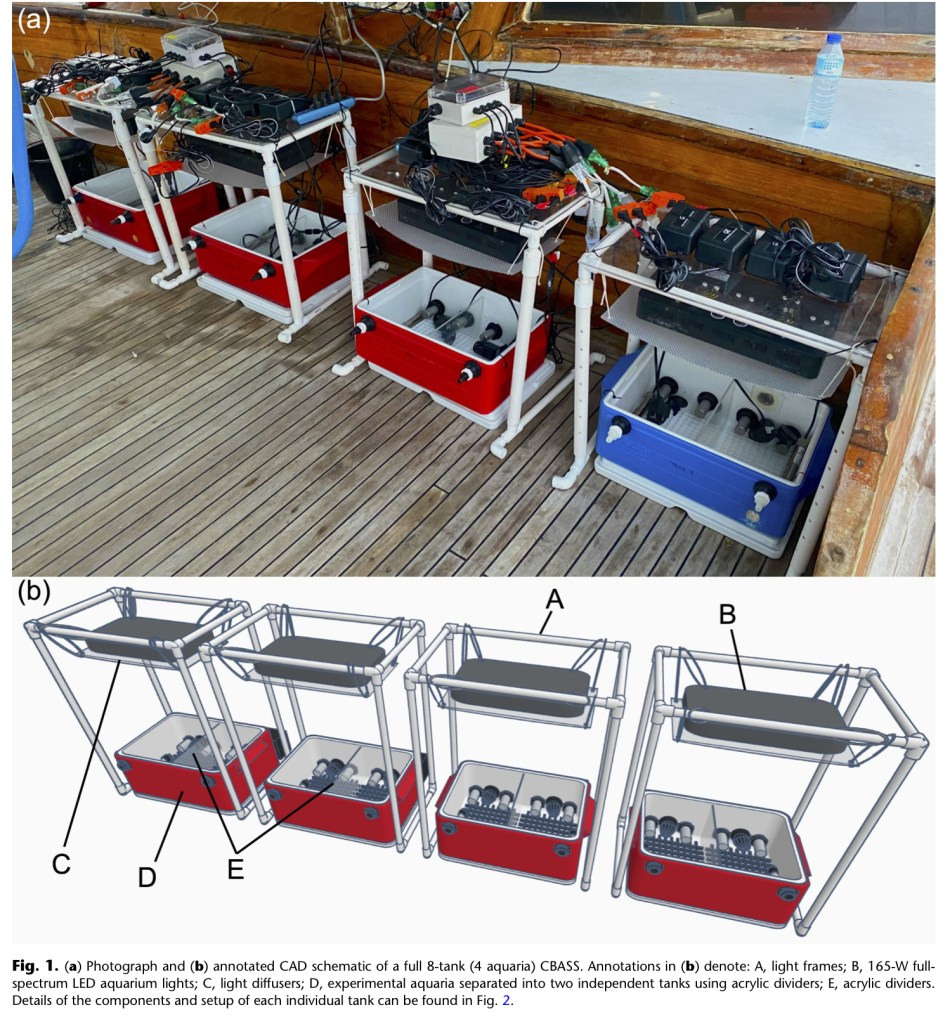

The CBASS is composed of three main modules; the experimental aquaria, temperature controllers, and lighting arrays. The system is capable of running four to eight flow-through aquaria that can manage between four to eight unique, dynamic temperature profiles in 18-hour increments depending on how it is configured. The basic setup was designed with maximum portability in mind for field use, research vessels, and remote locations. All the instructions for setup and configuration as well as the the code to run the arduino controller are maintained and updated in a github repository.

The image below shows a photograph of the basic CBASS setup and below that a CAD schematic with parts labeled.

There are also instructions to set up this system using Inkbird temperature controllers instead of the arduino controllers which reduces the cost and overall complexity by a great deal. The trade-off is in the consistency and granularity of the temperature controls.

The image below shows a closeup of one aquaria and light array and the recommended configuration for specimens in the tank. Below that is another labeled diagram of each of the parts that make up one tank.

To run a CBASS assay 2, users place a coral ramet (a fragment of coral that can establish a new colony3 ) and attach them to the egg carton crate material in the bottom of the tank with a rubber band. Treatments should be run within two – three hours of collection. Typical treatments include a baseline using the local maximum monthly mean (MMM) seawater temperatures from NOAA satellite data4 and then three elevated temperature profiles increasing in 3° – 4°C increments or seven profiles that increase in 1° – 2°C increments. These temperature profiles are designed to capture the full range of biological stress response in coral.

The metric recommended in this paper is called the Effective Dose 50 (ED50) because it is “non-destructive, repeatable, consistent, and relatable to bleaching.” 5 The ED50 is a statistical measure used to determine the dose (in this context, usually a stressor like light, temperature, or a chemical) at which 50% of the maximum effect is observed. 6

To understand this measure, I must first explain what the ratio “Fv/Fm” means. Fv/Fm is an indicator of the maximum potential quantum efficiency of PSII under optimal conditions. The Fv/Fm is a common measurement used to assess the maximum quantum yield of Photosystem II (PSII) in photosynthetic organisms like plants, algae, and corals. The Fv/Fm test is designed to allow the maximum amount of the light energy to take the fluorescence pathway. 7 8

When Fv/Fm and ED50 are combined, it refers to the dose of a stressor at which the Fv/Fm ratio decreases to 50% of its maximum value. This provides a quantitative measure of the sensitivity of the organism to the applied stressor. 9 In coral research, Fv/Fm ED50 can be used to assess the resilience or sensitivity of coral to various environmental stressors, such as temperature changes or pollutants. By determining the ED50 value, researchers can quantify how much of a particular stressor is needed to reduce the photosynthetic efficiency of coral by half, which is a crucial indicator of coral health.10 By using this metric, users can make empirical and statistical comparisons of thermal thresholds for coral populations and individual genotypes.

The image below is an example of a statistical analysis using Fv/Fm ED50 as the measurement metric. As a testament to the capabilities of the CBASS and the Fv/Fm ED50 metric, the researchers writing this paper were able to determine thermal thresholds for four coral species across six different site in across global regions in just 2 weeks time.

Citations

- Evensen, N.R., Parker, K.E., Oliver, T.A., Palumbi, S.R., Logan, C.A., Ryan, J.S., Klepac, C.N., Perna, G., Warner, M.E., Voolstra, C.R. and Barshis, D.J. (2023), The Coral Bleaching Automated Stress System (CBASS): A low-cost, portable system for standardized empirical assessments of coral thermal limits. Limnol Oceanogr Methods, 21: 421-434. https://doi.org/10.1002/lom3.10555 ↩︎

- An assay is a laboratory procedure for measuring the presence, amount, or activity of a substance ↩︎

- Nimrod Epstein, Baruch Rinkevich, From isolated ramets to coral colonies: the significance of colony pattern formation in reef restoration practices, Basic and Applied Ecology, Volume 2, Issue 3, 2001, Pages 219-222, ISSN 1439-1791, https://doi.org/10.1078/1439-1791-00045.ay is a laboratory procedure for measuring the presence, amount, or activity of a substance ↩︎

- NOAA Coral Reef Watch. Daily Global 5km Satellite Sea Surface Temperature (a.k.a. CoralTemp). NOAA Satellites and information service. Source: https://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/product/5km/index_5km_sst.php ↩︎

- Evensen, N.R., Parker, K.E., Oliver, T.A., Palumbi, S.R., Logan, C.A., Ryan, J.S., Klepac, C.N., Perna, G., Warner, M.E., Voolstra, C.R. and Barshis, D.J. (2023), The Coral Bleaching Automated Stress System (CBASS): A low-cost, portable system for standardized empirical assessments of coral thermal limits. Limnol Oceanogr Methods, 21: 421-434. https://doi.org/10.1002/lom3.10555 ↩︎

- Kate Maxwell, Giles N. Johnson, Chlorophyll fluorescence—a practical guide, Journal of Experimental Botany, Volume 51, Issue 345, April 2000, Pages 659–668, https://doi.org/10.1093/jexbot/51.345.659 ↩︎

- Maxwell, K., & Johnson, G. N. (2000). Chlorophyll fluorescence—a practical guide. Journal of Experimental Botany, 51(345), 659-668. ↩︎

- Kate Maxwell, Giles N. Johnson, Chlorophyll fluorescence—a practical guide, Journal of Experimental Botany, Volume 51, Issue 345, April 2000, Pages 659–668, https://doi.org/10.1093/jexbot/51.345.659 ↩︎

- Baker, N. R. (2008). Chlorophyll fluorescence: a probe of photosynthesis in vivo. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 59, 89-113. ↩︎

- Warner, M. E., Fitt, W. K., & Schmidt, G. W. (1999). Damage to photosystem II in symbiotic dinoflagellates: a determinant of coral bleaching. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 96(14), 8007-8012. ↩︎