Invasive species are a significant source of biodiversity loss in a given habitat. This is largely because they can quickly reach high population levels and outcompete native individuals. This rapid population growth will usually result in significant, harmful overall impact on ecosystems.

This study examines the population density factors of the invasive Indo-Pacific red lionfish – which was introduced an early 2000s to the Caribbean, western Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico – by field testing population density dependence. The purpose of this research is to determine whether there is a limit to lionfish populations and the thresholds (if any) at which limits are initiated for these marine predators. 1

The density of lionfish populations in the Caribbean, western Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico has already exceeded population density in their native ranges by an order of magnitude. These lionfish have a huge detrimental impact on coral reef fish populations, especially ecologically and economically significant species like parrot fish and grouper. The red lionfish is a highly effective ambush predator and so far at the time of publication of this research, there is no apparent effective population control.

Density dependence is an important concept in ecology that describes the rate at which the overall number of individuals in a population decreases and the loss rates increase as the population grows.

“Density dependence occurs when the population growth rate, or constituent gain rates (e.g. birth and immigration) or loss rates (death and emigration), vary causally with population size or density (N). … Direct density dependence is caused by competition, and at times, predation.”2

“Demographic density dependence is generally defined as an effect of present and/or past population sizes on the per-capita population growth rate, and thus at least one of the constituent demographic rates.”3

Density dependence is a balancing factor in an ecosystem that helps control populations; a balanced population will experience an increase in population growth rate where the overall population has low density and a decrease in population growth where there’s high density.

Results

Lionfish demonstrated population density dependence in their size and mass; lionfish in higher density areas grew more slowly and to a smaller length and mass.

However, lionfish growth rates were not differentially affected by density – meaning that the different treatments applied did not give different results in all cases – sites with higher density, experienced slower growth, and smaller fish

Figure 1. Effect of density on individual lionfish growth rates.

Graph A shows the growth rate for the length of the fish in mm/day which decreased linearly as the population increased.

Graph B shows the growth rate for the mass of the fish in mg/day which decreased exponentially as the population increased.

There was no evidence of density dependence in the loss rate of lionfish. In fact loss rates were low for all sites with only six out of 40 fish being lost. At least one missing fish was due to immigration and it’s suspected that that may be true for some others.

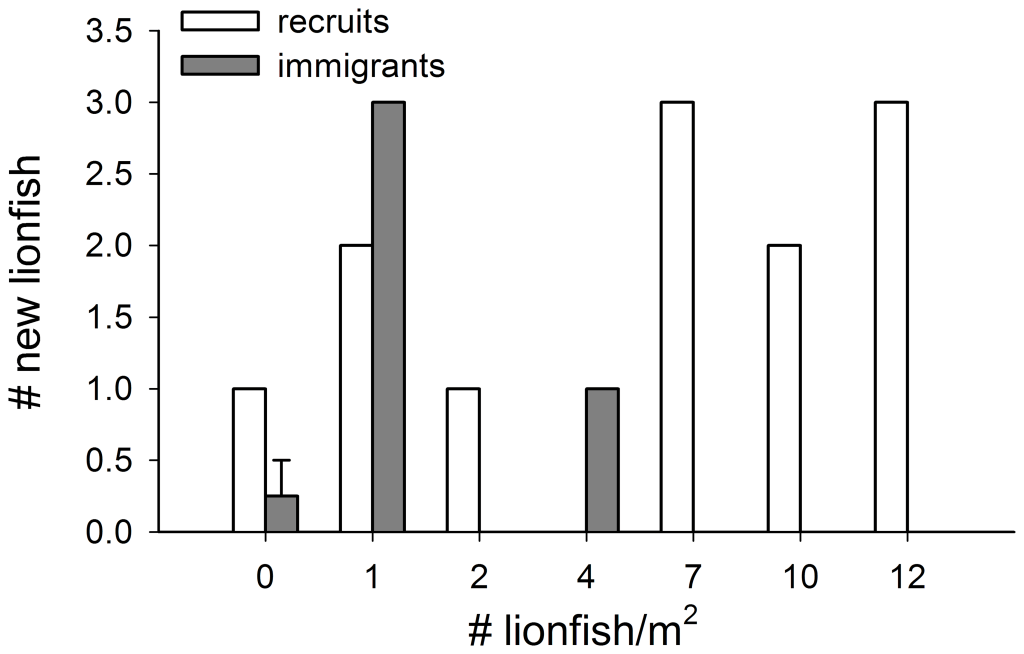

Similarly, there was no evidence of density dependence on recruitment (availability of larva, settlement behavior, and post settlement survival and growth) of juvenile fish. The same was true for juvenile and adult immigration during the experiment where a total of 14 lionfish recruits appeared.

Discussion

The observed slower growth rates and the smaller sizes of the fish were most likely due to increases in population density. This smaller size lionfish could have a larger impact on the reef ecosystem and the native species that live there. Most importantly, lionfish prey species will change as the lionfish population density changes.

Normally, as lionfish grow they tend to switch from eating smaller crustaceans to larger reef fish. If population density of lionfish continues to increase and the overall size of lionfish remains smaller, that will likely mean smaller crustaceans will experience higher predation rates.

The most likely cause of the density independence in lionfish populations is intraspecific competition or competition between individuals of the same species, and the mechanism is most likely exploitative competition, which is a form of indirect competition where one organism consumes a resource and creates scarcity for other organisms also wanting that resource. It is unlikely that the mechanism is interference competition because no aggression between lionfish was observed during the experiments.

Overall, there was no apparent threshold at which lionfish populations would decline and this – combined with the fact that there are effectively no predators for lionfish5 – means that the only likely control on the lionfish population is the availability of food. Unfortunately, as generalists there are a wide range of species that lionfish can eat. Over the course of this experiment, there was an observed decline in native fish recruitment.

It is possible that the observed low loss rates was due to the fact that this experiment used juvenile lionfish placed on isolated reefs that were comparable in size to natural patch reefs, and perhaps a continuous system would show a different loss rate for lionfish. However, at least one other study of a continuous habitat involving an estuary system with juvenile and adult lionfish, they showed similar site fidelity and low loss rates. Additionally, other density-dependent studies of coral reef fishes showed that small-scale experimental results are reliably accurate in larger scale settings.

Conservation efforts

The current method for lionfish management is to manually remove them. However, these efforts focus on adult lionfish and it may be worth additional study on the effect adult lionfish populations have on juvenile recruitment and settlement rates. If a loss of adult lionfish were to result in compensatory recruitment of juveniles, meaning that the rate of juvenile recruitment increased because of the low adult survival rate – the current removal efforts would be severely undermined.

Because density dependence typically affects fish most in the juvenile stages. It’s unlikely that adult lionfish would experience any losses until their prey populations are severely reduced. Therefore, manual removal is the best strategy at this time and conservationist should maintain ongoing monitoring of lionfish populations for any compensatory density dependence.

Citations

- Benkwitt, Cassandra E. June 2013. Density-dependent growth in invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans). PLos ONE 8(6):e66995. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066995. ↩︎

- Hixon, Mark A; and Johnson, Darren W (December 2009) Density Dependence and Independence. In: Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (ELS).John Wiley & Sons, Ltd: Chichester.DOI: 10.1002/9780470015902.a002121 ↩︎

- Murdoch, William W. “Population Regulation in Theory and Practice.” Ecology, vol. 75, no. 2, 1994, pp. 272–87. JSTOR, https://doi.org/10.2307/1939533. Accessed 9 Sept. 2024. ↩︎

- Benkwitt, Cassandra E. June 2013. Density-dependent growth in invasive lionfish (Pterois volitans). PLos ONE 8(6):e66995. ↩︎

- There is some speculation that large groupers could be predators for lionfish, but an experiment with NASA with large Nassau groupers showed that that did not have a significant impact on lionfish populations. ↩︎