Abstract

Using the 16S rRNA gene to identify an unknown bacterial sample

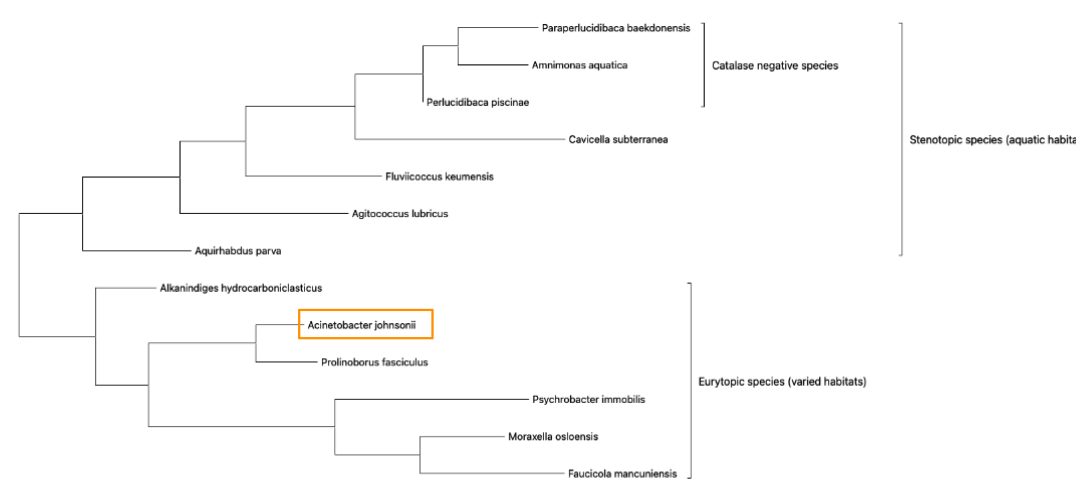

The purpose of this study was to identify a bacterial sample collected from a local storm water reservoir using the 16S rRNA gene to identify it. The genetic sequence was then used to explore the evolutionary relationships of the identified bacteria. A freshwater sample from Lake Pasadena was cultured, and DNA was extracted from a selected colony. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified via PCR and confirmed by gel electrophoresis (~1500 bp). Sequencing and BLAST analysis identified the bacterium as Acinetobacter johnsonii. Phylogenetic analysis using MEGA11 placed it within a eurytopic group of Gammaproteobacteria, capable of surviving diverse environments. Sub-tree groupings highlight habitat adaptability and catalase activity as a key ecological trait.

Introduction

Bacteria are single-celled prokaryotes with double-stranded circular DNA that lacks a nucleus (Sanders & Bowman, 2019). The simplicity of the organism combined with its short generation times and ease of maintenance makes studying certain aspects of this organism – like its DNA – significantly easier than that of Eukaryotic cells (Sanders & Bowman, 2019). Often, bacterial classification is based on characteristics like shape, Gram-staining properties, cell wall properties and metabolic activities (Woese et al., 1990) (Gladson, 2008). However, the ability to identify bacteria using its DNA through PCR amplification has improved identification – especially in cases of less well known bacteria (Woo et al., 2008).

Sample collection location is an important factor when dealing with bacteria – the sample collected for this experiment came from a freshwater aquatic habitat. In the case of aquatic bacterial colonies, level of eutrophication and salinity levels are among the most significant factors that influence species and colony size (Tang et al., 2021). Depending on species, bacteria in these habitats can play a role in nutrient cycling as well as primary production (Tang et al., 2021).

The 16S gene is a common marker used when working with bacteria for several reasons – it is a highly conserved sequence in the rRNA – meaning it has remained the same over the course of evolution (Janda & Abbott, 2007) such that almost all bacterial species have this gene. The 16S rRNA gene itself contains a number of genes – but its primary purpose is related to the RNA component of the 30S small subunit of the bacterial ribosome, essential for protein synthesis (Woese, 1987). The 16S gene is large enough (1,500 base pairs) (Janda & Abbott, 2007) that it is possible to use universal primers for PCR amplification while also having sufficiently variable regions to distinguish between bacterial species (Johnson et al., 2019). The 16S gene is also used for phylogenetic studies, and environmental microbiome analysis (Johnson et al., 2019).

In this lab, the 16S rRNA gene was sequenced using the Sanger, or dideoxy method, in order to identify the bacterial species present in the collected sample. By amplifying and analyzing the 16S gene, the sampled bacteria was classified based on sequence variations, allowing for a better understanding of the microbial community structure and its ecological role in Lake Pasadena.

The sequenced DNA was input into the NCBI online tool “BLAST” which stands for “Basic Local Alignment Search Tool”. This powerful research software is used to compare regions of nucleotide sequences from one organism to the DNA sequences of many other organisms in the database. The software calculates the statistical significance of matches so researchers can identify organisms and their possible evolutionary relationships to other organisms (National Center for Biotechnology Information [NCBI], n.d.).

The identified and matched DNA sequences were exported from BLAST as a FASTA file and input into the MEGA (Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis) software. This software is used to analyze DNA and protein sequences, and construct phylogenetic trees for evolutionary hypothesis testing (Stecher et al., 2020).

Procedure

Sample Collection

The sample was collected on January 22nd, 2025 at 8:00am from the south culvert of Lake Pasadena in Saint Petersburg, Florida.

The sample was collected close to water level on a calm, cloudy day. The temperature was 5.6℃ and it had rained the night before.

The sample was then spread evenly using a uniform zig-zag pattern over an agar plate and incubated at 26℃ for seven days.

DNA Extraction

After seven days, the sample had grown numerous, mostly similar colonies.

Fig 3. Bacterial colonies cultured from the sample. On the left: all colonies, on the right: the colony selected for the PCR procedure is indicated.

The DNA extraction procedure

The DNA extraction process began with the addition of 180 µL of enzymatic lysis buffer, which contained 20 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 2 mM NaEDTA (a chelating agent), 1.2% Triton X-100 (a detergent), and 20 mg/mL lysozyme to break down bacterial cell walls. The mixture was incubated at 37°C for 30 minutes in a dry bath to facilitate enzymatic digestion. Following this, 25 µL of Proteinase K and 200 µL of Buffer AL were added, and the solution was incubated at 50°C for 30 minutes in a wet bath. After incubation, 200 µL of ethanol was added to the solution, which was then centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 1 minute.

The lysate was transferred to a silica spin column, where 500 µL of Wash Buffer 1 was applied, followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 1 minute. This step was repeated using 500 µL of Wash Buffer 2, followed by another 1-minute centrifugation at 12,000 × g to remove residual contaminants. Finally, the DNA was eluted by adding 200 µL of elution buffer to the column. A final centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 1 minute ensured the purified DNA was collected into a clean tube.

PCR Procedure

In this PCR procedure, two primers were used – a forward and a reverse primer. The sequence for the 16S Forward Primer was: AGAGTTTGATC and the 16S Reverse Primer sequence was: GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT.

In order to amplify the DNA in the sample the PCR Master mix was created with 100 µL of PCR mix, 8 µL of the Forward Primer and 8 µL of the Reverse Primer, 64 µL of nuclease free water. Finally, 5 µL of the extracted DNA was added to the positive vial and no DNA was added to the negative control vial. Once the DNA was added to the PCR Master mix the following parameters were used for the thermocycler settings.

Thermocycler Settings

| Stage | # of Cycles | Temp ºC | Time (min:sec) | Notes |

| Stage 1: Denaturation | 1 | 95 ºC | 5:00 | DNA strands separate |

| Stage 2: Annealing | 35 | 95 ºC 56 ºC72 ºC | 0:300:451:00 | primers attach to the key sequences of the DNA strand |

| Stage 3: Elongation (DNA Synthesis) | 1 | 72 ºC | 10:00 | Taq polymerase uses nucleotides in solution to create the new DNA strand |

Gel Electrophoresis Procedure

After completing the PCR thermal cycling process, gel electrophoresis was performed to analyze the amplified DNA. For the procedure, 7 µL of the PCR product was loaded into a well of the agarose gel. The gel was then run at 125 volts for 20 to 30 minutes to allow DNA fragments to migrate based on size.

PCR Cleanup Procedure

The PCR cleanup procedure was performed to purify amplified DNA by removing excess primers, nucleotides, and other reaction components. To begin, 40 µL of the PCR reaction was combined with 200 µL of Buffer PB, followed by the addition of 10 µL of sodium acetate. The solution was thoroughly mixed using a vortex before being pipetted into a silica spin column. The column was then centrifuged at 3,000 RPM for 1 minute, allowing the DNA to bind to the membrane.

Next, 750 µL of Buffer PE was added to wash the sample, and the column was centrifuged at 13,000 RPM for 1 minute. The flow-through was discarded, and a second centrifugation at 13,000 RPM for 2 minutes was performed to ensure complete drying of the membrane. For DNA elution, 50 µL of Buffer EB was added to the column, followed by centrifugation at 13,000 RPM for 1 minute to collect the purified DNA into a clean tube. Finally, 2 µL of primase was added to the sample.

Mega / Blast Procedure

The sequenced DNA was input into the NCBI BLAST online tool in order to identify the organism from the sampled DNA. Once this was done, the full DNA sequence of the identified organism was used to find twelve additional organisms with similar DNA sequences. These additional DNA sequences were output as a FASTA file. Then, the DNA sequences from the identified organism and the twelve additional organisms were input into the MEGA software for alignment and generation of a phylogenetic tree.

Results and Discussion

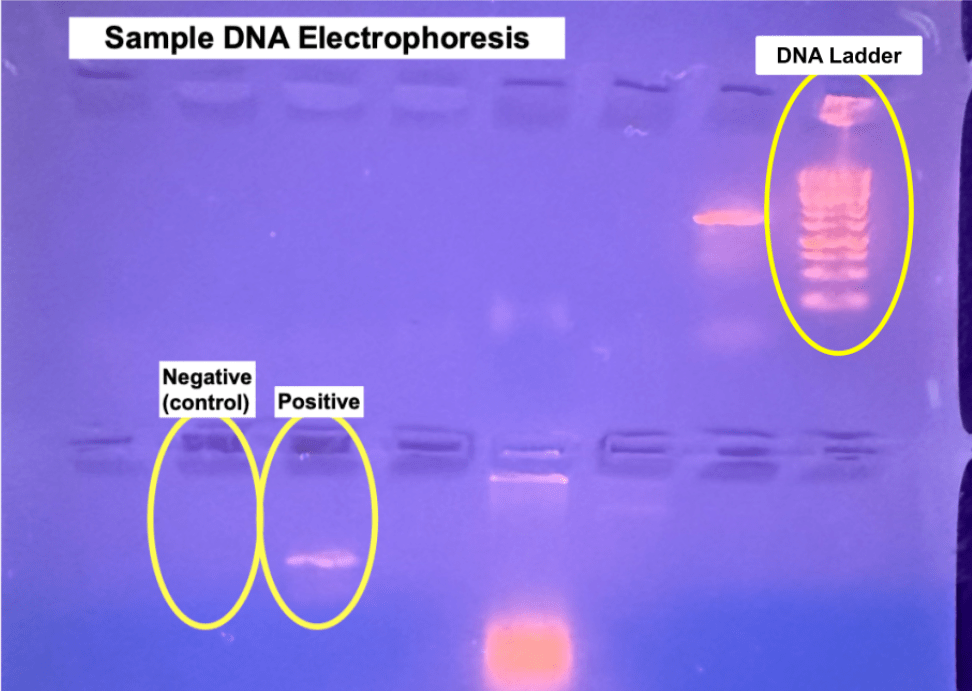

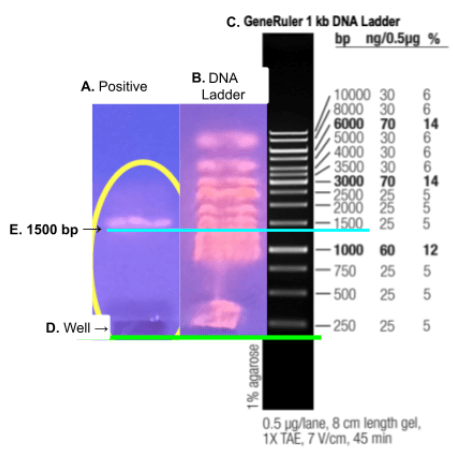

The gel electrophoresis showed a bright band at 1500 base pairs which confirmed that DNA was present. The image below shows the results of the gel electrophoresis.

In the upper right corner, the DNA ladder is circled and below that, the two circled wells indicate the negative control which contains no DNA in order to ensure there was no contamination enduring the PCR process and the positive which contained the extracted DNA.

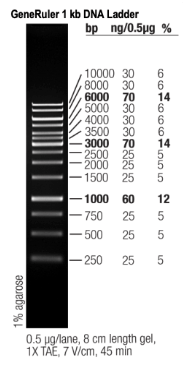

The DNA ladder used was the Fisher Scientific 2 kb DNA ladder which is also known as the Thermo Scientific GeneRuler 1 kb DNA Ladder. The manual for this DNA ladder includes an image with the known base pair bands labeled. The image on the right shows the bands labeled by nucleotide base pair quantities.

The image below shows the Thermo Scientific GeneRuler 1 kb DNA Ladder image aligned with the gel electrophoresis image and the positive PCR containing the extracted DNA. The green line indicates the aligned wells and the blue line indicates the aligned 1500 bp which is exactly the expected base pair number expected.

Once the presence of the expected 1500 base pairs was confirmed, the DNA sample was sent away to be sequenced. The sample was successfully sequenced with a result of 1081 nucleotides. The quantity of nucleotides was higher than the minimum 700 required for species identification by 381 making the identification results stronger and more certain.

The identity of the sampled and extracted DNA was Acinetobacter johnsonii – an opportunistic pathogen that can often be found in hospitals although it is typically only dangerous for seriously ill individuals. This bacterial strain can also be found in soil, water, sewage, as well as poultry, red meats, and milk products. (ScienceDirect, 2025)

The twelve genetically similar organisms selected for a phylogenetic analysis were; Paraperlucidibaca baekdonensis, Amnimonas aquatica, Perlucidibaca piscinae, Cavicella subterranea, Fluviicoccus keumensis, Agitococcus lubricus, Aquirhabdus parva, Alkanindiges hydrocarboniclasticus, Prolinoborus fasciculus, Faucicola mancuniensis, Moraxella osloensis, and Psychrobacter immobilis. The genetic sequences of all thirteen organisms were input to MEGA and a phylogenetic tree was generated. The image below shows the phylogenetic tree along with sub-tree groupings for stenotopic, eurytopic, and catalase-negative organisms. These groupings are discussed in greater detail later.

The closest genetic match is the organism Prolinoborus fasciculus which was formerly classified under the class Betaproteobacteria but has since been reclassified as Gammaproteobacteria due to its 16S DNA sequence similarity to Acinetobacter johnsonii (Glaeser et al., 2020).

In order to identify additional possible sub-tree groupings the following categories were researched for each of the 13 organisms and compiled into the table below for easier sorting and comparison purposes. Once this was done, it became obvious that the upper two thirds of the tree is composed of aquatic organisms and the lower third is composed of organisms that can thrive in a wide range of habitats. It is worth noting that the middle of the tree contains an organism that was isolated in crude oil – a naturally occurring liquid mixture of hydrocarbons (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2025). This could be an example of an evolutionary intermediate step, or simply an illustration of the amazing evolutionary adaptive capacity of bacteria.

Once the table was sorted by common habitat and then by the ability to metabolize catalase, the sub-tree groupings were identified as Stenotopic which is an adjective used to describe organisms that have a narrow range of criteria for their habitat (Oxford University Press, retrieved 2025). This group describes the bacteria commonly found in aquatic habitats. The Eurytopic group is thus identified due to their ability to live in a wide range of habitats (Oxford University Press, retrieved 2025).

It is interesting to note that only the aquatic dwelling group includes organisms that are catalase-negative meaning that they lack the enzyme catalase, and so cannot break down hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂) – which is toxic to the cell – into water and oxygen. Therefore, these organisms are unlikely to be found in habitats with high levels of hydrogen peroxide (Hartline 2025) such as waste water or other forms of sewage.

Bacterial Strain Comparison Table

| Bacterial strain | Gram +/- | Aerobic/ Anaerobic | Shape | Motility | Oxidase +/- | Catalase +/- | Location first Isolated from | Citation |

| Paraperlucidibaca baekdonensis strain | – | Aerobic | rod | non-motile | + | – | Seawater of the East Sea in Korea | (Oh, 2011) |

| Amnimonas aquatica strain | – | Strictly Aerobic | rod | motile (single flagellum) | + | – | Han River in South Korea | (Lee, 2019) |

| Perlucidibaca piscinae strain | – | Aerobic | coccus | non-motile | + | – | Eutrophic pond | (Song et al., 2008) |

| Cavicella subterranea strain | – | Strictly Aerobic | rod | non-motile | + | + | Deep mineral-water aquifer in Central Portugal | (França, Albuquerque, & da Costa, 2015) |

| Fluviicoccus keumensis strain | – | Aerobic | coccus | non-motile | + | + | Freshwater | (Kim, Kim, Kim, Joung, Han, & Kim, 2016) |

| Agitococcus lubricus strain | – | Aerobic | coccus | motile (twitching motility) | + | + | Freshwater | (Baumann, Baumann, Mandel, & Allen, 1981) |

| Aquirhabdus parva strain | – | Aerobic | Rod | motile | + | + | Freshwater lake in Korea. | (Kim, Shin, & Yi, 2020) |

| Alkanindiges hydrocarboniclasticus strain | – | Aerobic | short rod | motile | + | + | Crude oil-contaminated desert sands | (Yadav, Kim, & Lee, 2021) |

| Acinetobacter johnsonii | – | Strictly Aerobic | coccobacillus | non-motile | – | + | Commonly found in soil, water, sewage, and various foods, including poultry and red meat | Vaneechoutte et al., 2015 |

| Prolinoborus fasciculus strain | – | Aerobic | curved rod | motile (polar flagellum) | + | + | Commonly found in aquatic systems, soil, and wastewater | (Glaeser et al., 2020) |

| Psychrobacter immobilis strain | – | Aerobic | Oval | non-motile | + | + | Poultry Carcass | (Bouvet & Grimont, 1986) |

| Moraxella osloensis strain | – | Aerobic | coccobacillus | non-motile | + | + | Human respiratory tract | (Hadano et al., 2012) |

| Faucicola mancuniensis strain | – | facultatively aerobic | Rod | motile (polar flagellum) | + | + | Tonsils of a healthy adult female | (Humphreys, Oates, Ledder, & McBain, 2015) |

Conclusion

The bacterium isolated from Lake Pasadena was identified as Acinetobacter johnsonii, a species known for its ability to thrive in a wide range of environments — from soil and wastewater to human skin, feces, and blood. The collection site is an area that experiences periodic flooding and drying, and is exposed to fairly extreme temperatures: it was just above freezing at the time of sampling, but the site also receives full subtropical sun.

Its presence in a culvert just above the waterline of a highly eutrophic stormwater pond, along with traits like catalase activity, suggests strong resilience to environmental stress. These extreme and fluctuating conditions align well with A. johnsonii’s classification as a eurytopic organism, capable of surviving in dynamic aquatic habitats. This finding illustrates how molecular tools like 16S sequencing can reveal adaptable, stress-tolerant microbes thriving in our own local ecosystems.

References

Baumann, P., Baumann, L., Mandel, M., & Allen, R. D. (1981). Taxonomy of aerobic marine eubacteria. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 31(2), 177–192. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-31-2-177

Bouvet, P., & Grimont, P. A. D. (1986). Taxonomy of the genus Acinetobacter with the recognition of Acinetobacter baumannii sp. nov., Acinetobacter haemolyticus sp. nov., Acinetobacter johnsonii sp. nov., and Acinetobacter junii sp. nov. and emended descriptions of Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Acinetobacter lwoffii. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 36(3), 388–393. https://doi.org/10.1099/00207713-36-3-388

França L, Albuquerque L, da Costa MS. Cavicella subterranea gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from a deep mineral-water aquifer, and emended description of the species Perlucidibaca piscinae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015 Nov;65(11):3812-3817. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000493. PMID: 28875925.

Gladson, B. (2008). Pharmacology for rehabilitation professionals (2nd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences.

Glaeser SP, Pulami D, Blom J, Eisenberg T, Goesmann A, Bender J, Wilharm G, Kämpfer P. The status of the genus Prolinoborus (Pot et al. 1992) and the species Prolinoborus fasciculus (Pot et al. 1992). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020 Sep;70(9):5165-5171. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004404. Epub 2020 Aug 26. PMID: 32845831.

Glen Stecher, Koichiro Tamura, and Sudhir Kumar (2020) Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) for macOS. Molecular Biology and Evolution 37:1237-1239 (Stetcher et al., 2020)

Hadano Y, Ito K, Suzuki J, Kawamura I, Kurai H, Ohkusu K. Moraxella osloensis: an unusual cause of central venous catheter infection in a cancer patient. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:875-7. doi: 10.2147/IJGM.S36919. Epub 2012 Oct 17. PMID: 23109812; PMCID: PMC3479945.

Hartline, L. (n.d.). 1.18: Catalase test. In Microbiology Laboratory Manual. LibreTexts. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://bio.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Microbiology/Microbiology_Laboratory_Manual_(Hartline)/01%3A_Labs/1.18%3A_Catalase_Test

Humphreys GJ, Oates A, Ledder RG, McBain AJ. Faucicola mancuniensis gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from the human oropharynx. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2015 Jan;65(Pt 1):11-14. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.066837-0. Epub 2014 Sep 29. PMID: 25267870.

Janda, J. M., & Abbott, S. L. (2007). 16S rRNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification in the diagnostic laboratory: Pluses, perils, and pitfalls. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 45, 2761–2772. https://doi.org/10.1128/jcm.01228-07

Johnson, J. S., Spakowicz, D. J., Hong, B. Y., Petersen, L. M., Demkowicz, P., Chen, L., … & Keim, P. S. (2019). Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nature Communications, 10(1), 5029.

Kim MK, Kim TW, Kim TS, Joung Y, Han JH, Kim SB. Fluviicoccus keumensis gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from freshwater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2016 Jan;66(1):201-205. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.000694. Epub 2015 Oct 22. PMID: 26498187.

Kim M, Shin SK, Yi H. Mucilaginibacter celer sp. nov. and Aquirhabdus parva gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from freshwater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2020 Oct;70(10):5479-5487. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.004437. Epub 2020 Sep 4. PMID: 32886597.

Lee Y, Park HY, Jeon CO. Amnimonas aquatica gen. nov., sp. nov., Isolated from a Freshwater River. Curr Microbiol. 2019 Apr;76(4):478-484. doi: 10.1007/s00284-019-01652-5. Epub 2019 Feb 19. PMID: 30783797.

National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). (n.d.). BLAST: Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi

Oh KH, Lee SY, Lee MH, Oh TK, Yoon JH. Paraperlucidibaca baekdonensis gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from seawater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011 Jun;61(Pt 6):1382-1385. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.023994-0. Epub 2010 Jul 2. PMID: 20601489.

Oxford University Press. (n.d.). Eurytopic. In Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://www.oed.com/search/dictionary/?scope=Entries&q=eurytopic

Oxford University Press. (n.d.). Stenotopic. In Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://www.oed.com/search/dictionary/?scope=Entries&q=stenotopic

Sanders, M., & Bowman, J. (2019). Genetic analysis: An integrated approach (3rd ed.). Pearson.

ScienceDirect. (n.d.). Acinetobacter johnsonii. In ScienceDirect Topics. Elsevier. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/acinetobacter-johnsonii

Song J, Choo YJ, Cho JC. Perlucidibaca piscinae gen. nov., sp. nov., a freshwater bacterium belonging to the family Moraxellaceae. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2008 Jan;58(Pt 1):97-102. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65039-0. PMID: 18175691.

Stecher G., Tamura K., and Kumar S. (2020). Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) for macOS. Molecular Biology and Evolution 37:1237-1239.

Tamura K. and Nei M. (1993). Estimation of the number of nucleotide substitutions in the control region of mitochondrial DNA in humans and chimpanzees. Molecular Biology and Evolution 10:512-526.

Tamura K., Stecher G., and Kumar S. (2021). MEGA 11: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Version 11. Molecular Biology and Evolution https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/msab120.

Tang, X., Xie, G., Shao, K., Tian, W., Gao, G., & Qin, B. (2021). Aquatic bacterial diversity, community composition and assembly in the semi-arid Inner Mongolia Plateau: Combined effects of salinity and nutrient levels. Microorganisms, 9(2), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms9020208

Thermo Fisher Scientific. (n.d.). GeneRuler 1 kb DNA Ladder (250 µg) user guide (Publication No. MAN0013004). https://assets.thermofisher.com/TFS-Assets/LSG/manuals/MAN0013004_GeneRuler_1kb_DNALadder_250ug_UG.pdf

U.S. Energy Information Administration. (n.d.). Oil and petroleum products explained. Retrieved April 10, 2025, from https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/oil-and-petroleum-products/

Vaneechoutte, M., Nemec, A., Kämpfer, P., Cools, P., & Wauters, G. (2015). Acinetobacter, Chryseobacterium, Moraxella, and other nonfermentative Gram-negative rods. In J. H. Jorgensen, K. C. Carroll, G. Funke, M. A. Pfaller, M. L. Landry, S. S. Richter, & D. W. Warnock (Eds.), Manual of Clinical Microbiology (11th ed., pp. 813–837). American Society for Microbiology. https://doi.org/10.1128/9781555817381.ch44

Woo, P. C. Y., Lau, S. K. P., Teng, J. L. L., Tse, H., & Yuen, K.-Y. (2008). Then and now: Use of 16S rDNA gene sequencing for bacterial identification and discovery of novel bacteria in clinical microbiology laboratories. Clinical Microbiology and Infection, 14(10), 908–934. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-0691.2008.02070.x

Woese, C. R. (1987). Bacterial evolution. Microbiological Reviews, 51, 221–271. https://doi.org/10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987

Woese, C. R., Kandler, O., & Wheelis, M. L. (1990). Towards a natural system of organisms: Proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 87(12), 4576–4579. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.87.12.457

Yadav S, Kim JS, Lee SS. Alkanindiges hydrocarboniclasticus sp. nov. Isolated From Crude Oil Contaminated Sands and Emended Description of the Genus Alkanindiges. Curr Microbiol. 2021 Jan;78(1):378-382. doi: 10.1007/s00284-020-02266-y. Epub 2020 Nov 11. PMID: 33179156.