Abstract

The coral microbiome is a powerful mechanism for resiliency with significant capacity to protect its host from pathogens, parasites, toxins, eutrophic waters, heat stress, and bleaching. This study will investigate whether heat tolerant coral species that retain their beneficial microbiome during a heat stress event can aid less heat tolerant species in recovering beneficial microbiome members via horizontal transmission during or post-heat stress. Due to the conservation protections placed on the endangered coral species that are the focus of this research, experiments will be conducted using Exaiptasia diaphana as a coral model organism. The Coral Bleaching Automated Stress System (CBASS) will be used to apply standardized heat stress assays in order to identify E. diaphana individuals with higher heat tolerance (Group A) and lower heat tolerance (Group B). Beneficial bacteria will be cultured from Group A tissue samples. The beneficial bacteria culture will be divided into two groups, randomly designated for group A or B, and marked with trackable markers before inoculating E. diaphana with their respective marked bacteria. The study has two phases: phase one will measure changes in bacterial concentrations under heat stress, and phase two will determine whether beneficial microorganisms (BMCs) transfer between individuals. In phase one, it is expected that Group A will retain more bacteria, while Group B will lose more. In phase two, it is expected that bacteria will transfer from Group A to Group B, with Group A losing less bacteria and absorbing minimal bacteria from Group B. This research aims to advance coral restoration techniques by leveraging interspecies interactions to enhance coral resilience and support biodiversity in reef ecosystems.

Introduction

Scleractinian coral are key ecosystem engineers (Jones, Lawton, and Shachak 1994) whose structural complexity provides habitat, shelter, and food (Graham and Nash 2013) for between 550,000–1,330,000 species worldwide (Fisher et al. 2015) which represents over 25% of all marine life (Fisheries 2023). This incredible diversity and species abundance make coral reefs critical economic drivers of tourism and fishing industries (Santavy et al. 2021). Coral reefs are also exceptionally good at protecting coastlines – dissipating the force of waves by up to 97% (Ferrario et al. 2014). As climate change progresses and storm intensity and frequency increase, coral reefs have the capacity to protect homes and lives as well as preventing billions of dollars in damage (L. Burke and Spalding 2022).

However, none of this is possible if coral reefs become extinct. In the past 30 years, we have already lost over 50% of our coral reefs globally – 14% of that loss has happened in the past ten years (Reef Resilience Network, n.d.).

Despite this incredible loss, there are ongoing efforts to extend the natural adaptive capacity of reef-forming coral using new tools, methods, and environments to improve their ability to survive in the face of climate change (Voolstra et al. 2021). This effort focuses on the coral holobiont – which includes the coral animal host, algal symbionts (Symbiodiniaceae), and an assemblage of bacteria and viruses (Voolstra et al. 2021). This holistic approach is critical given the relative simplicity of the coral animal combined with the significant complexity and capacity of microorganisms that make up the coral microbiome to drive mechanisms for resiliency against pathogens, parasites, toxins, eutrophic waters, heat stress, and bleaching (Voolstra and Ziegler 2020). This capacity of the microbiome to impact the coral holobiont is summarized in the Coral Probiotic Hypothesis as “a dynamic relationship [that] exists between symbiotic microorganisms and environmental conditions” (Reshef et al. 2006).

The Coral Probiotic hypothesis supports the theory that coral have evolved the ability to rapidly change their microbiome in response to environmental conditions in order to select for the most advantageous microbial partners (Voolstra and Ziegler 2020). These advantageous microbial partners are commonly referred to as Beneficial Microorganisms for Coral (BMCs) and are defined as a collection of microorganisms that “contribute to coral health by aiding in nutrient uptake and growth, reducing the effects of stress and pollution or other toxins, having anti-pathogenic properties, and aiding in early life stage development (Peixoto et al., 2021).

The coral microbiome is complex with many different bacterial members found in different compartments (mucus layer, tissue, skeletal) of the coral holobiont. Some bacterial species appear in multiple coral species – sometimes in the same compartment and sometimes not – while other bacterial species are entirely unique. Although hundreds of different bacterial strains have been isolated in the coral microbiome, not enough is known about the bacterial strains that have been identified and sequenced to date (McCauley et al. 2023). In particular, it is currently unclear whether the bacteria found across different species of coral perform the same functions for each species.

Despite having different microbiome assemblages, there is a growing body of evidence that coral benefit from BMCs, even when the bacterial composition used is not specific to the coral species being treated (Doering et al. 2021), though the beneficial effects are greater with a native consortium of BMCs (Rosado et al. 2019).

One particularly compelling example of the impact of BMCs is the study conducted in 2021, when Santoro et al. demonstrated the effect of BMCs during a simulated heat stress event in which every single coral genet in the placebo group either bleached bone white or died while the treatment group only paled or bleached but did not die and recovered significantly faster than the placebo group (Santoro et al. 2021)

The degree to which BMCs can benefit a coral may also be due to the degree to which a coral can change its microbiome – some coral show minimal evidence of change in microbiome assemblage, while other species are “microbiome conformers” and will more readily adapt their microbiome during stress events (Santoro et al. 2021). These microbiome conformers take a gamble that they will be able to uptake more of the beneficial bacteria needed for a given stress event, despite an ever increasing risk that this will also provide pathogenic bacteria an opportunity to infect the coral host (Santoro et al. 2021).

While lab treatments using BMCs have been successful in controlled environments, there are significant challenges to applying this in the field. It is difficult to confirm whether inoculation has been successful, scaling the treatment to cover an entire reef or region is extremely complex, and the longevity of the treatment is unknown.

Heat stress

In a comparative study testing stress responses in corals due to elevated levels of nutrients and heat stress, the most significant and consistent factor in coral mortality was heat alone (Palacio-Castro et al. 2022). Therefore, this study will examine the stress responses in a coral microbiome related to heat alone.

During a heat stress event, the bacterial assemblage in a coral microbiome changes – some of these changes are beneficial, some pathogenic (Voolstra and Ziegler 2020). The degree to which the microbiome changes is uncertain – there are a number of studies with differing conclusions as to this – however most agree that factors such as species, type of stressor, and severity of stress are important (Voolstra and Ziegler 2020). Regardless, if there are no additional confounding factors, the microbiome will eventually revert back to its normal assemblage (Voolstra and Ziegler 2020).

After a heat stress event the coral host must spend energy and resources on cellular and tissue repair. If the coral has bleached and lost its symbiont, there will be very little, if any, energy to spare rendering the coral highly susceptible to disease and parasites – this extended recovery period is described as Post-heat stress disorder (PHSD) by (Santoro et al. 2021).

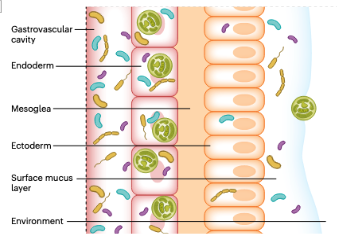

Coral compartments

The specific location bacterial samples are taken from is a critical consideration – coral have many different compartments with different bacterial assemblages and different environmental factors. Sampling from different compartments can provide insight into biological or metabolic processes as well as interactions between the coral, its symbiont, and the environment. Samples taken without this degree of spatial specificity can result in erroneous conclusions as to microbiome populations and functions (Armitage and Jones 2019; Hughes et al. 2022)

Key microbiome members

Although there is a wide range in diversity of coral-associated microorganisms, there are a number of key bacteria that can be found in coral hosts across sub-phylum, depth, and habitat (McCauley et al. 2023). Most notably, in a recent, study spanning almost all known coral reef systems and over twelve thousand cnidarian microbiome samples from 186 studies, including over 6.5 billion sequence reads, McCauley et al. found that, out of all the genetic sequences identified as bacterial, the family Endozoicomonadaceae was, by far, the most common in each of the four cnidarian classes: Anthozoa, Cubozoa, Hydrozoa, and Scyphozoa with over 74% having been identified in scleractinian corals (McCauley et al. 2023).

Endozoicomonas

Endozoicomonas was first identified in 2007 by (Kurahashi and Yokota 2007). Since then, they have been globally identified as common coral microbiome members with higher concentrations of this bacteria being strongly associated with healthy coral colonies and healthy coral reefs (Neave et al. 2016). Although there is evidence that, depending on clade, the bacteria Endozoicomonas may have different functions within a coral host or may perform different functions across species (Ide et al. 2022), it is generally accepted that this bacteria has a beneficial, photoprotective role in the coral microbiome via its ability to metabolize dimethylsulphoniopropionate (DMSP) into free-radical scavenging compounds.

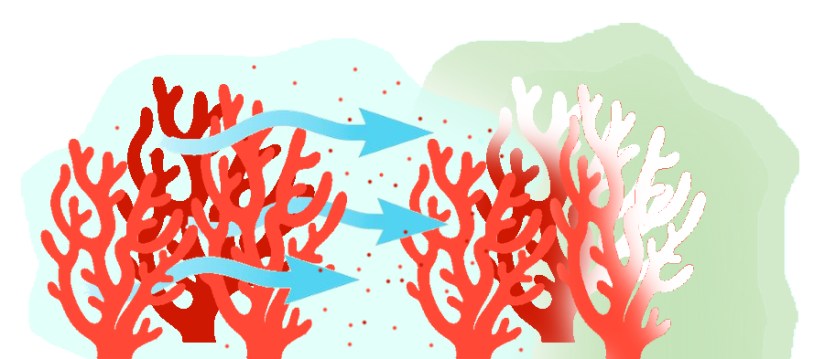

Endozoicomonas are found in host tissues in bacterial aggregates (Neave et al. 2016) or dense clusters called cell-associated microbial aggregates (CAMAs) whose formation may be triggered by high concentrations of DMSP (Maire et al. 2023). Because these CAMAs have not yet been found in coral larvae, it is thought that Endozoicomonas is acquired via horizontal transmission at the recruit or adult stage (Maire et al. 2023). The possibility of horizontal transmission is further supported by the significant concentrations at which is has been found in seawater surrounding corals combined with the relatively large size of its genome – indicating that Endozoicomonas may have a free-living period in their life cycle that requires additional genes (Neave et al. 2016; Weber et al. 2019).

Horizontal transmission of bacteria

While there is a large body of knowledge regarding horizontal transmission of the algal symbiont, symbiodinium among coral (De Oliveira et al. 2020), there is much less research currently into the horizontal transmission of BMCs. Most examples of beneficial horizontal transmission involve plant rhizomes in soil and sponges in marine ecosystems (Breusing et al. 2022). This is likely in part due to the significant advantages of vertical transmission in terms of efficiency and consistency. However, horizontal transmission provides a greater advantage to an organism when flexibility is required in order to adapt to new conditions. Horizontal transmission can facilitate a faster spread of beneficial microbiota – much faster than evolution via vertical transmission (Breusing et al. 2022). Indeed – this is already evident in the increased rates of disease transmission among corals (S. Burke et al. 2023). Though disease transmission is not the only known example of horizontal transmission. In the study conducted by McCauley et al. to unify and reanalyze thousands of sequences recorded from coral samples, they found that Alcyonacean and Scleractinian corals hosted about 30% of all shared microorganisms, which they theorize could mean coral species in these orders act as a bacterial reservoir for other cnidarian species (McCauley et al. 2023).

Objectives

This study will investigate whether heat tolerant species that retain their beneficial microbiome during a heat stress event can aid less heat tolerant species in recovering beneficial microbiome members via horizontal transmission and thus be less susceptible to bleaching and recover more quickly post-heat stress.

Phase one of this study will measure the change in bacterial concentrations under heat stress. Phase two of this study will determine whether BMCs move from one individual to another.

Methods

Model organism Exaiptasia diaphana

Due to the conservation protections placed on the endangered coral species that are the focus of this research, this study will utilize Exaiptasia diaphana (formerly Aiptasia diaphana) a sea anemone commonly used as a model organism for coral; (Dungan et al. 2020). E. diaphana fits the primary requirements for a model organism in that it is small, highly abundant, and easy to care for, and has short generation times via sexual and asexual reproduction (Weis et al. 2008). More importantly, however, E. diaphana shares many characteristics with coral and responds similarly to experimental inputs (Dungan et al. 2020; Weis et al. 2008).

For this study, a minimum of two of the four common Clonal E. diaphana strains with distinct genotypes will be used; Hawaii, the Atlantic Ocean, Red Sea, and Great Barrier Reef (Dungan et al. 2020). Individual genotypes of E. diaphana will be tested to identify individuals with higher or lower heat tolerances using the same strategy applied by (Voolstra et al. 2020).

Simulating heat stress

In order to identify heat tolerant E. diaphana individuals, this study will use the Coral Bleaching Automated Stress System (CBASS) in an enclosed aquarium system to apply standardized, short-term acute heat stress assays (Dörr et al. 2023). The baseline temperature for these assays will be determined by the mean summer maximum (MMM) temperature of the regions where the specific E. diaphana strains used in this experiment are from (Evensen et al. 2023; Voolstra et al. 2020). After each heat stress assay, the heat tolerance of each E. diaphana will be determined by measuring the photosynthetic efficiency using Pulse Amplitude Fluorometry (PAM) fluorometry measurements (Schansker 2020) following the specific protocols for taking measurements as described by (Cunning et al. 2021).

The E. diaphana individual identified as having a high heat tolerance will become group A, and the individual identified as having a lower heat tolerance will become group B. Group A and B individuals will then undergo cloning via pedal laceration to create replicates for phase one and two trials and control groups.

BMC selection

For the purpose of this study, BMCs will be collected from the E. diaphana individual with the higher heat tolerance. The bacterial samples will be taken from the endodermal tissue layer and where relevant, will follow the protocols described by (Voolstra et al. 2023; Bergman et al. 2022) to extract and preserve DNA. The collected bacteria will be cultured and sequenced for identification following protocols described in (Santoro et al. 2021). Although it is hoped that the cultured samples will include Endozoicomonas, there are a number of additional bacterial strains that could serve equally well for this experiment. Therefore, the BMC selected for this experiment must meet the following selection criteria: there must be evidence of at least one beneficial property: anti-pathogenic, photoprotective, nitrogen or phosphorus cycling, it must be culturable in a lab, it must be possible to mark and visualise (preferably in-vivo) the specific strain, and its genome must be sequenced well enough to easily identify it.

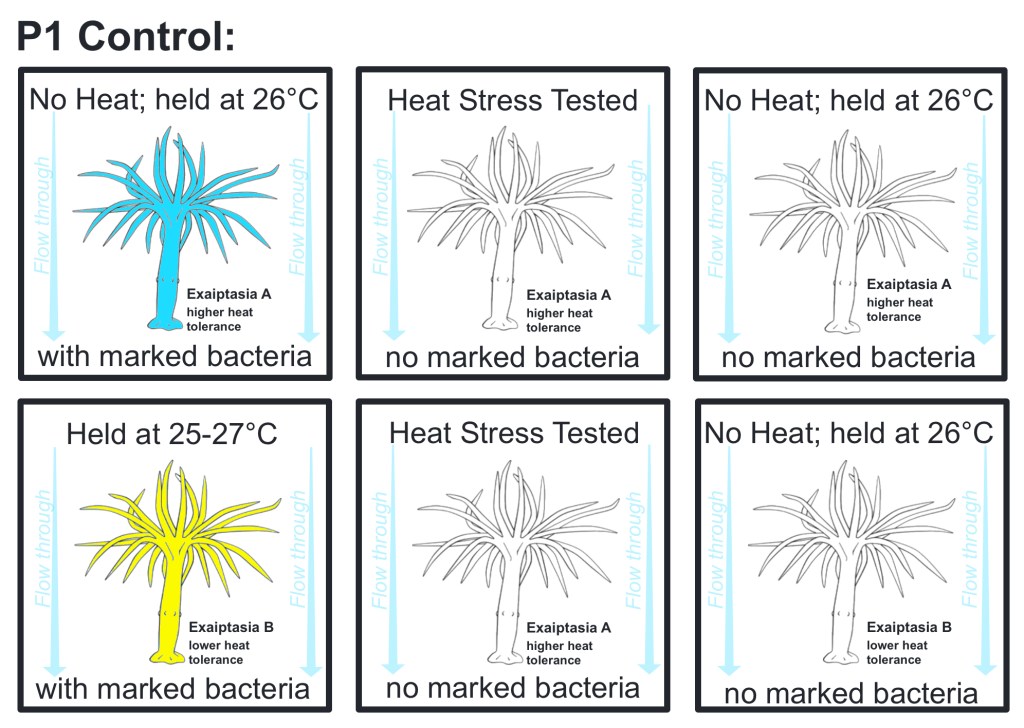

Phase 1: Measure change in bacterial concentrations under heat stress

Once a beneficial bacteria is identified, it will be cultured in larger quantities for use in phase one and two trials and control groups. Once sufficient quantities are cultured, it will be randomly divided into two groups consisting of the same bacterial strain. Each group will be given a unique, trackable marker and assigned to either group A or B.

Five replicates of E. diaphana from Group A and Group B will then be inoculated with their corresponding marked bacteria. This inoculation step will be confirmed and an initial concentration measurement will be taken. E. diaphana will be placed in separate flow-through aquarium systems to ensure that any lost bacteria cannot be reabsorbed. Standardized heat stress assays will be applied using CBASS. Concentrations of marked bacteria will be monitored during and after heat stress testing by measuring concentrations in both individuals at set time intervals.

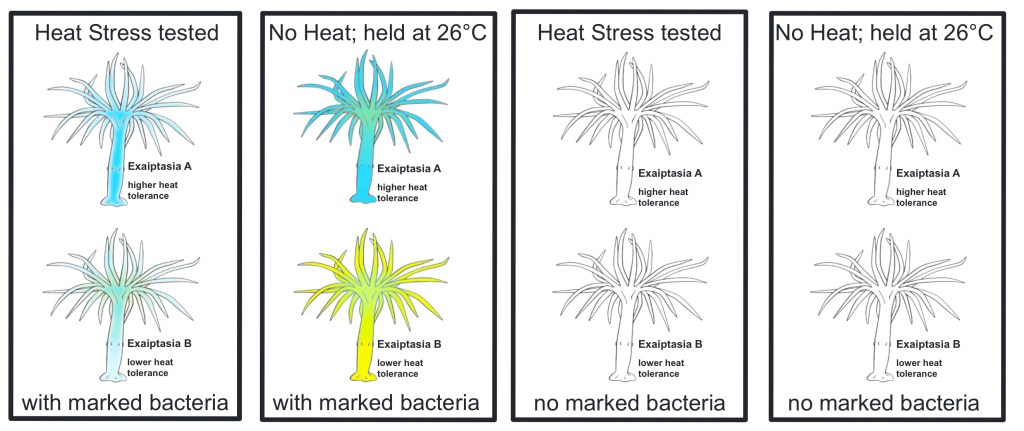

Fig.2: Phase 1 trial – experimental workflow diagram

Phase 1 control groups

There are three control groups consisting of at least five replicates for this experiment: inoculated E. diaphana from groups A & B without heat stress that are held at optimal temperature 26℃, E. diaphana from groups A & B without marked bacteria inoculation that are heat stress tested, and E. diaphana from groups A & B without marked bacteria inoculation that are held at optimal temperature 26℃.

Fig.3: Phase 1 trial control groups – experimental workflow diagram

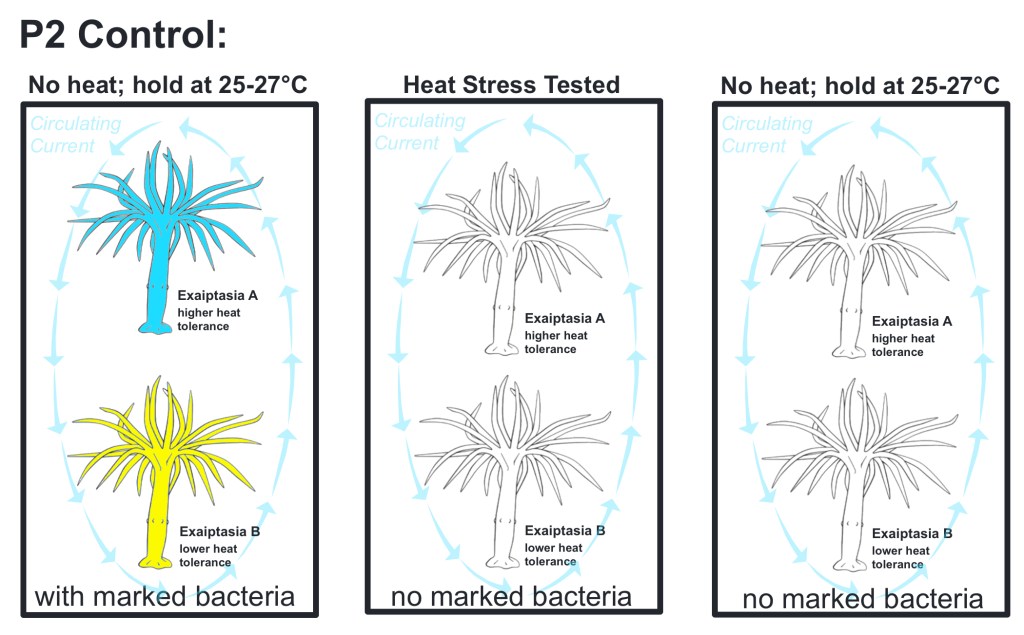

Phase 2: Determine whether BMCs move from one individual to another

In the second phase, five replicates consisting of the same groupings (A & B) inoculated with the same marked bacteria will be used. The only difference in experimental design for phase two is a shared aquarium system with a circulating current.

E. diaphana will be placed in the shared aquarium system with a circulating current to ensure that any lost bacteria have opportunities to be reabsorbed. Standardized heat stress assays will be applied using CBASS.

Concentrations of marked bacteria will be monitored during and after heat stress testing by measuring concentrations in both individuals at set time intervals.

Fig.4: Phase 2 trial – experimental workflow diagram

Phase 2 control groups

Phase two uses at least 5 replicates of the same three control groups from phase one – the only difference being that the A & B individuals are each placed in the shared enclosure during the experiment.

Fig.5: Phase 2 trial control groups – experimental workflow diagram

Expected Results

Phase 1: Expected Results

Expected results for E. diaphana A with the higher heat tolerance include loss of a small amount of inoculated bacteria and minimal signs of heat stress.

Expected results for E. diaphana B with the lower heat tolerance include loss of a significant amount of inoculated bacteria and moderate signs of heat stress.

Phase 2: Expected Results

Expected results for E. diaphana A with the higher heat tolerance include loss of a small amount of inoculated bacteria and minimal signs of heat stress.

Expected results for E. diaphana B with the lower heat tolerance include loss of a significant amount of inoculated bacteria and uptake of a measurable amount of Bacteria with the A marking and low levels of heat stress.

Discussion

This research proposal utilizes horizontal transmission as a potential mechanism for creating a living “BMC reservoir”. If this research proves viable in the coral model organism E. diaphana, then future research would involve testing this with a variety of coral species in controlled laboratory tests and then in field studies. The ultimate purpose of this experimental progression is to establish a sustainable, living “BMC reservoir” in a reef system that continually supports the surrounding coral community. This approach could provide a more scalable solution for coral reef management.

Other applications of this research could include applying BMC treatments to the reservoir coral prior to known heat stress events which, while still more time and labor intensive than a strict reservoir approach, could reduce overall effort by only requiring BMC treatments to key coral interspersed throughout a reef.

While this vision presents a promising method for enhancing coral resilience, it is important to acknowledge the complexities and unknowns of coral microbiomes, making it a challenging but potentially valuable strategy for mitigating heat stress and improving coral survival in the face of climate change.